SINGAPORE — “China plus-one,” “friend-shoring” and “reshoring” may be catchphrases of the day, with the underlying trends they describe being well-supported by macro-level trade data. But as sourcing shifts out of China due to risk mitigation and other factors, one thing is increasingly apparent: Moving production out of China is costly, even to the point of leading some to reconsider it.

The reality is that for any number of product categories, relocating sourcing brings with it less efficient logistics, occasional lower quality, and overall higher costs at a time when cost control is rapidly assuming a higher priority for shippers.

That is why some executives with long experience in Asia logistics believe that if factors like risk mitigation were to recede as an urgent supply chain priority — for example, if there were to be a de-escalation of geopolitical tensions — China could, at least in the short term, recapture lost manufacturing given the well-established efficiency and quality of its overall system.

“The short-term rush out of China has in some cases been too rushed and infrastructure/cost and capabilities were not ready to absorb the business from China and thus if there were immediate changes in China; some of that would likely come back as an interim step,” said a senior Asia-based forwarding executive.

However, “two to three years more of fixing the bugs in the new countries will make that reversal much less likely,” he added, reflecting a view that diversification of supply firmly remains a long-term trend.

Still, it’s not happening without bumps in the road. According to anecdotes shared with the Journal of Commerce by a freight forwarder, such frustrations led a white goods manufacturer who had a pre-COVID sourcing split of roughly 40% Thailand, 33% Vietnam and 17% China to “actually (go) back to China for a significant amount of sourcing.”

Three specific reasons were cited: a more dependable supply chain for raw materials and parts, less tangled transportation solutions out of Asia, and sourcing capacity – especially following the surge in demand during the pandemic.

Issues in Vietnam led a footwear and apparel maker to acknowledge the pain associated with transitioning from a 57% China/29% Vietnam split to 45% China/35% Vietnam today. “Ocean capacity is a major issue,” for the shipper, the forwarder said.

“From a transportation and lead time angle, [the company was] much better off in Xiamen, which can boast over five times [the] direct call capacity than Haiphong.”

A seller of artificial Christmas trees, meanwhile, was sourcing 93% of its product from China as of 2019, but as of 2023 is sourcing 58% from China and 41% from Cambodia. However, the forwarder said, “they do not see a further shift away from China as they also cited capacity and supply chain efficiencies from China were still far superior than those in Cambodia.”

“Not surprisingly, priority [purchase orders] … are still coming from China as they do not have enough confidence that the factory, infrastructure or transportation options from Cambodia can deliver consistently,” the forwarder source added. “Also worth noting that as a result of the shift, this particular importer has had to push up its shipping program for Christmas trees, and rather significantly at that.”

Sourcing shift comes with new costs

A study prepared for the annual US Federal Reserve Jackson Hole Symposium held from Aug. 24-26 found that moving production out of China brought additional cost.

“Decreases in product-level import shares from China are associated with rising unit values for imports from Vietnam and Mexico, which likely reflects rising costs of production in these locations,” the study concluded. “This ongoing reallocation of global supply chain activity comes attached with costs that need to be monitored and assessed more rigorously.”

Part of the additional cost stems from less-efficient logistics, including fewer direct connections that result in more frequent transshipments, as well as chronically congested terminals and inland connectors. Sources say companies buying from factories are likely to experience more problems than large industrial companies that make a long-term commitment to a new market by establishing their own production and associated supply chains.

Part of the underlying issue is that transportation infrastructure is well known to be far less developed throughout Southeast Asia, even if it’s expanding rapidly across the region. According to maritime consultancy Drewry, as of 2022, 76 container terminals in China were able to handle ships greater than 14,000 TEUs, while there were only 31 across south and southeast Asia. China is the only country in the world to have built significant container port capacity ahead of demand, while in other developing countries new terminals fill up almost immediately after they open.

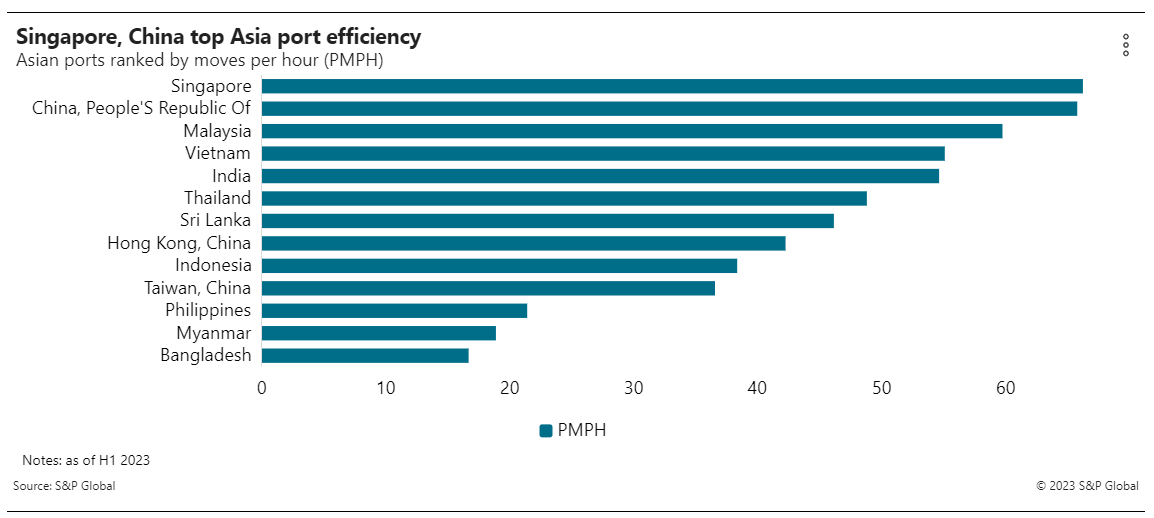

One example of divergent levels of efficiency is berth productivity, measuring how quickly terminals load and offload ships. China and Singapore have the most productive ports in the region, with ports in other countries, including the Philippines, Myanmar and Bangladesh generating substantially lower productivity, contributing to vessel delays and larger supply chain disruption, according to Port Performance data from S&P Global, parent company of the Journal of Commerce.

“Building redundancy into supply chains isn’t costless,” economist Marc Levinson, author of The Box and a scheduled TPM24 speaker, told the Journal of Commerce. “If a manufacturer makes a product in two or three countries rather than in one location, it may lose economies of scale, and its supply chain logistics get more complicated.”